Controversy Surrounds Texas' Bluebonnet Curriculum

The implementation of the Bluebonnet curriculum, a state-created educational program that includes Bible references, has sparked significant debate across Texas. As of the 2025-26 academic year, several school districts, including Conroe ISD, have decided to adopt this curriculum, despite growing concerns about its content and implications.

A recent research paper from the Baker Institute of Public Policy at Rice University highlights the potential impact of the Bluebonnet materials, suggesting that they may favor Christian perspectives over other religious traditions. The report, authored by David Brockman, a professor at Texas Christian University, argues that the curriculum could undermine the separation of church and state and reduce religious diversity in public education.

This is the third report on the topic from Brockman, who has expressed concerns that the curriculum promotes Christianity at the expense of other faiths. He claims that the materials may create an "insider/outsider dynamic" among students, which could be detrimental to the core mission of public education.

Districts Weighing the Decision

While some districts have opted out of using the Bluebonnet curriculum, others are reviewing it for potential adoption. For example, Fort Bend ISD is currently evaluating a pilot set of the materials to determine if they meet the district's instructional standards for possible implementation next year.

Most districts that chose not to use the curriculum cited pedagogical reasons, such as the fact that the materials are printed rather than digital. Some, like Cy-Fair ISD, had existing contracts for reading materials that were still valid, so they did not need to implement new resources immediately.

Conroe ISD, however, has approved the use of the Bluebonnet curriculum, planning to introduce it in classrooms starting in August. This decision comes with trade-offs, as some schools will need to reduce instructional time for fine arts to accommodate the curriculum’s 120 minutes of daily instruction.

In San Antonio, at least two districts—Harlandale ISD and South San ISD—have adopted the materials, adding to the growing list of districts implementing the curriculum.

Legal and Educational Implications

A recent Supreme Court ruling in Mahmoud v. Taylor could further complicate matters for districts that have implemented the Bluebonnet curriculum. The court ruled 6-3 that parents can opt their children out of lessons that conflict with their faith. This decision may lead some families to request exemptions from the religious elements of the curriculum, creating new challenges for educators.

Brockman’s report delves into the history of teaching the Bible in U.S. schools, noting that it was often presented in a devotional context before key Supreme Court rulings in the 1960s. Even after these rulings, he recalls instances where sectarian prayers were still practiced in schools, sometimes excluding certain religious groups.

He argues that the Bluebonnet curriculum promotes Christianity over other religions, sending a message that only Christianity is worthy of students’ attention. However, he acknowledges that the curriculum is not explicitly designed to convert students or promote devotional practices.

Perspectives from Educators

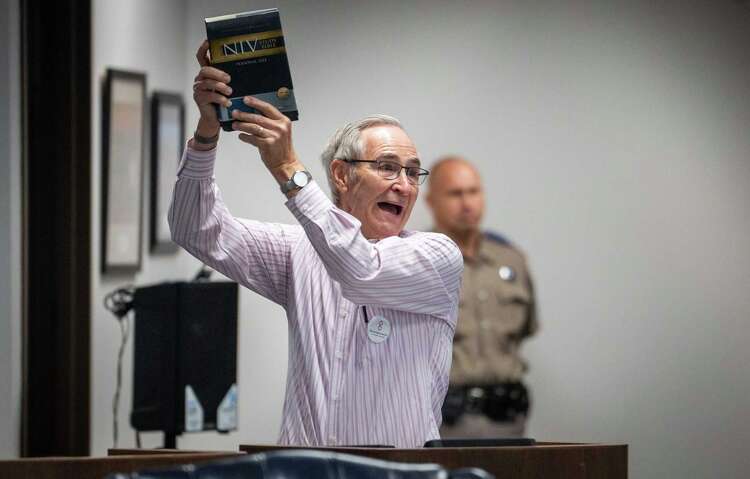

Marvin McNeese, a professor of education at the College of Biblical Studies in Houston and a former lecturer at Rice University, offers a different perspective. He served on the advisory board for the Bluebonnet materials and believes that the focus on Christianity makes sense in the context of U.S. history.

McNeese evaluated the curriculum for accuracy, rigor, and appropriateness and found it to be well-constructed. He emphasized that the curriculum aims to teach U.S. history to U.S. students, acknowledging that other countries would not emphasize Christianity in the same way.

He pointed to specific examples, such as a lesson on the founding of Texas that included Meso-American religions of the region’s indigenous communities. McNeese argued that these lessons help students understand the cultural and historical roots of their environment.

He also noted that the curriculum presents information about other religions, even if they are not covered as extensively as Christianity. For instance, a lesson on the Golden Rule includes references to Buddhism, Hinduism, Islam, Judaism, and Sikhism, even if these faiths were not the primary motivation for its application in American culture.

Balancing Faith and Education

McNeese acknowledged the concerns of parents from non-Christian backgrounds but maintained that it is normal for students in the U.S. to encounter Christian ideas as part of their education. He suggested that these experiences could serve as opportunities for parents to educate their children about their own faiths at home.

Regarding the age of students, he compared the approach to the concept of the tooth fairy, arguing that young children can learn to differentiate between facts and beliefs. He emphasized that academic integrity involves considering sources and making informed decisions about what to accept or reject.

Brockman agreed that religion should be taught in schools but raised concerns about how the Bluebonnet curriculum handles religious content. He questioned what would happen if a student asked a teacher about the historical accuracy of biblical events, highlighting the potential for controversy and the need for teachers to navigate complex religious discussions.

Despite these concerns, Brockman acknowledged that the curriculum includes a small portion of religious material within a broader framework of science-based reading instruction. He warned, however, that the curriculum could open the door to costly legal challenges that might challenge the Establishment Clause under the current Supreme Court.

As the debate over the Bluebonnet curriculum continues, the balance between religious education and secular values remains a critical issue for educators, parents, and policymakers across Texas.