Wearing a blue De Zavala Eagles hat, Heather Tolksdorf stood at the speaker's podium at a Fort Worth Independent School District board meeting last month, pleading with board members to vote down a proposal to close her daughters' school .

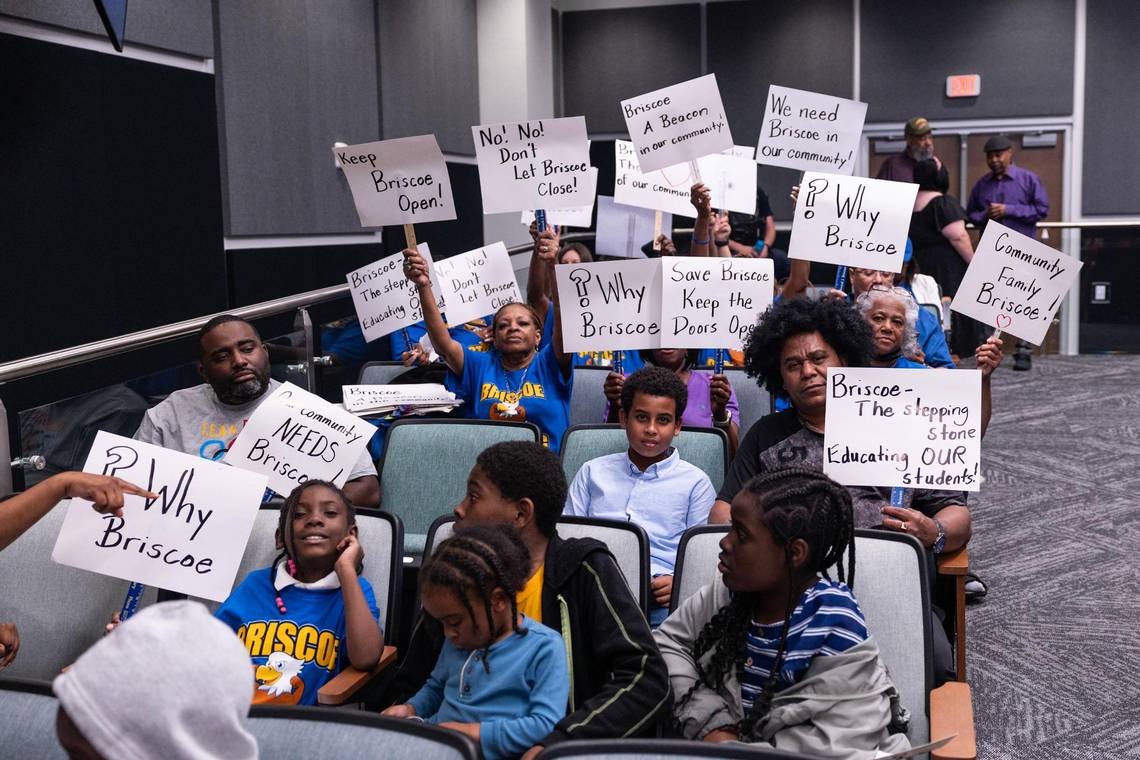

Tolksdorf was the 23rd speaker of the evening, and more than two dozen more would follow after her. Filling the room were parents, students and teachers from campuses across the district, though mainly from De Zavala and Briscoe elementary schools. Most were there for the same thing: to try - ultimately unsuccessfully - to save their kids' schools from closure.

Tolksdorf's daughters, Sophia and Olivia, were in De Zavala's dual-language kindergarten class last year. When Tolksdorf and her husband told them that the school could close in the next few years, the girls were confused, she told the Star-Telegram.

"The question all 5-year-olds ask is, why?" Tolksdorf said. "And we as a family say, well, we don't know."

De Zavala is one of 18 schools the district is scheduled to close and consolidate over the next four years. Located in Fort Worth's Fairmount neighborhood, the school is in a part of the city where Fort Worth ISD has seen its enrollment dwindle over the past five years, even as the population of school-aged children has grown. The trend illustrates one of the challenges facing the district: Presented with more options for how to educate their kids, a growing number of families are choosing schools outside of Fort Worth ISD.

School closures follow declining FWISD enrollment

Fort Worth ISD's board voted last month to close 18 campuses over the next four years. The closures come after years of declining enrollment - the district has about 15% fewer students now than it did during the 2019-20 school year. District officials say closing and consolidating small and under-enrolled campuses will allow them to redirect money toward academic priorities like reading programs.

District officials have pointed to a number of issues to explain the enrollment declines. Housing patterns are one big factor. Although Fort Worth is one of the fastest-growing major cities in the country, most of that growth is happening in parts of the city that are served by suburban school districts.

But a Star-Telegram analysis of enrollment data from Fort Worth ISD and population data from the U.S. Census Bureau shows that there are large swathes of the city where the school-aged population is growing, but the district's enrollment is shrinking. One such area is the 76104 ZIP code, which encompasses Fort Worth's Fairmount, Morningside, Hillside and Historic Southside neighborhoods, as well as the city's medical district.

Fort Worth ISD Enrollment Trends

This map displays enrollment changes at Fort Worth ISD campuses from the 2019-20 to 2023-24 school years, along with ZIP code population shifts for residents ages 5-19. Blue indicates enrollment or population growth, while red shows a decline. Yellow diamonds highlight campuses with additional notes or insights about their status. You can zoom in and tap or click on items for more information.

SOURCES: Fort Worth ISD, U.S. Census Bureau

The 76104 ZIP code covers neighborhoods that are underserved in a variety of ways. In a 2019 study, researchers at UT Southwestern Medical Center found that residents had the lowest life expectancy in the state at 66.7 years, nearly 12 years less than the national average. In an investigation published in 2020, residents told the Star-Telegram they suffered from a lack of access to health care , driven by a lack of transportation, health insurance or awareness of programs that could help.

The population of residents between ages 5 and 19 in the 76104 ZIP code has grown by about 13% since 2019, census figures show. But during the same period, six of the seven zoned campuses in the area have posted enrollment declines of 10% or more. Two schools - Briscoe and Morningside Middle School - have lost more than a third of their enrollment. Only Trimble Tech High School posted modest enrollment growth during that period.

Tolksdorf said she thinks a big part of the reason De Zavala is losing enrollment is a lack of marketing and community engagement on Fort Worth ISD's part. Olivia and Sophia love De Zavala, Tolksdorf said. She and her husband chose the school for them based on the combination of diversity and academic excellence. De Zavala has had an A rating in the state's accountability scores for the past five years, and Tolksdorf said her daughters have learned enough through the school's dual-language program that they're able to have conversations with friends in Spanish. But when Tolksdorf tells her neighbors about what a great experience her daughters are having at the school, they're surprised. She thinks that's a sign that the district isn't doing a good enough job telling its own story.

In the meetings leading up to the vote, a number of De Zavala parents pointed out that there's been a great deal of interest in the school's dual-language program, but district officials haven't expanded it beyond one class per grade. Several parents suggested that expanding the program could draw more families to De Zavala, making it more financially feasible to keep it open. But like many districts across the state, Fort Worth ISD has struggled to find enough teachers who are credentialed to teach dual-language classes.

Fort Worth charter schools see enrollment growth

Over the past decade, charter schools have made up a small but growing portion of Fort Worth's public education system. During the 2023-24 school year, 22,554 students were enrolled in Fort Worth charter schools, about a third as many as were enrolled in Fort Worth ISD, according to figures compiled by the Fort Worth Education Partnership. In the city's eighth City Council district, which stretches from Historic Southside south to where Fort Worth borders with Burleson and encompasses most of the 76104 ZIP code, the number of students enrolled in charter schools grew from zero in 2015 to 3,516 this year.

Senaida Sanches is one of the thousands of parents who have moved their kids from Fort Worth ISD to a charter school over the past decade. On the last day of school at Uplift Mighty Preparatory, Sanches and two of her three kids were sitting in her car on the street outside the south Fort Worth charter school, waiting for the third to come out.

Sanches transferred her oldest daughter from Fort Worth ISD's Clifford Davis Elementary School to Uplift Mighty when she was in fourth grade. The younger two went to pre-K at Glen Park Elementary before Sanches transferred them to Uplift Mighty.

At first, Sanches' main reason for the change was the convenience of having all three of her kids together on a single campus from kindergarten through high school, she said. But when her oldest daughter moved to Uplift, Sanches noticed an immediate difference. Sanches had suspected for years that her daughter had dyslexia, but she said teachers at Clifford Davis pushed her concerns to the side and put off screening her for reading disabilities. But when she moved to Uplift, teachers gave her a screening immediately and, when she was diagnosed with dyslexia, connected her with extra support, Sanches said.

Crystal Chapa, the mother of a student at Idea Achieve in Haltom City, said concerns about reading also prompted her to transfer her daughter out of Fort Worth ISD. When Chapa's daughter, Chanel Alvarado, was in first grade at Versia Williams Elementary School in 2021, Chapa noticed she was struggling with reading. At first, Chanel's teacher assured her that many students were struggling coming out of the pandemic, and that Chanel would have no problem catching up.

But as the year progressed, Chanel didn't seem to be gaining much ground, Chapa said. The fact that she was struggling to read was beginning to affect her self-esteem, she said. As the end of the year approached, Chanel's teacher proposed the idea of having her repeat first grade. But at the school's end-of-year awards ceremony, Chapa noticed that even the highest-achieving fifth-graders struggled to read. At that point, she began to suspect that reading was a broader issue at Versia Williams.

"It's just not my daughter," she said. "It's everyone."

State test scores bear out what Chapa observed. Although the school has made strides since 2021, just 5% of the Versia Williams' third-graders - two students - scored on grade level in reading on that year's STAAR.

So Chapa and her husband decided to transfer Chanel to Idea Achieve at the beginning of second grade. Since then, Chapa has noticed better communication from teachers at the charter school. School leaders also seem quicker to connect students with tutoring if they need extra help, she said.

Chanel will start fifth grade at Idea Achieve in August. She's excited about school in a way that she never used to be, Chapa said, and the extra support she's gotten from her teachers has helped her get on track in reading.

Replacing old school buildings could put FWISD ahead

Kellie Spencer, Fort Worth ISD's deputy superintendent, said in neighborhoods like Morningside and Historic Southside, where enrollment is declining but the school-age population is growing, increased competition from charter schools is the most likely explanation.

Fort Worth ISD leaders have made a top priority of improving reading scores, which could make the district a more attractive choice for families who are considering a range of school options. But Spencer said replacing old, dilapidated buildings with newer ones could also put the district in a better position to compete with charter schools. When parents look at what school would be the best fit for their child, the strength of academic programs is generally their top priority, she said. But some parents also believe that how a school building looks on the outside reflects what's going on inside, she said. That assumption gives some charter schools an advantage, at least at first, she said, since they're often in brand-new buildings.

But the facilities plan leaves neighborhoods with the question of what happens to the school buildings that are slated for closure. Over the summer, Spencer said district officials will be meeting with members of the communities affected by the school closure decisions to talk about what their needs are. Aside from the loss of the schools themselves, campus closures often leave neighborhoods with vacant school buildings, something Fort Worth ISD officials have promised not to do.

Spencer said the district may have options for those buildings other than tearing them down or selling them. The district could reopen some of those campuses as schools of choice or use them in some other way, she said. In some cases, the district might be able to partner with another agency or outside group to turn those buildings into some other service, like a clinic or a food pantry, she said.

But in many cases, Spencer said, the buildings on the closure list are so old and in such bad shape that it doesn't make financial sense to repair them. De Zavala and Briscoe elementary schools and Morningside Middle School are all in poor condition, according to a facilities report the district's consultant released in October. Both Briscoe and Morningside are projected to be in critical condition within the next decade.

Briscoe school closure could force students into long walk

In conversations and public comments sessions leading up to the board's decision, parents and teachers expressed concern that school consolidation would mean some students would have long, dangerous walks to school. At Briscoe, for example, teachers said students would be left with a long walk through a bad neighborhood once the school closes. Students from Briscoe are scheduled to go to Carroll Peak Elementary School. In general, school districts in Texas only provide transportation for students who live more than two miles away from school. Many Briscoe students live a few blocks from their current school, but a mile and a half from Carroll Peak over a route that crosses a railroad track.

During last month's meeting, Toyneisha Lomax, a mother and long-term substitute teacher in the district, said she was worried about the safety of students who would have to walk through the neighborhood between Briscoe and Carroll Peak. Crime is a problem in the neighborhood, she said, and once Briscoe closes, parents and volunteers might not be able to walk students to school, as they do now.

"As a mom, this does not sit very well with me. As an educator, this does not sit very well with me," she said.

But Spencer, the deputy superintendent, said the district can make exceptions to the two-mile rule for students who would be left with no safe way to get to school otherwise. In cases where a student's only path to school is unsafe on foot, the district can redesign bus routes and add stops to make sure they have transportation.

"We've heard from families who say, ‘My child is going to have to cross a railroad track,'" Spencer said. "That's not going to happen. That is not a safe, walkable route to school."

Fort Worth school closures offer teachable moment

By the time the campus closure proposal came up for a vote at last month's meeting, only a handful of parents remained on hand. A few minutes before midnight, the board voted 8-0 to approve the plan. Board member Wallace Bridges was absent.

Tolksdorf, the De Zavala mom, said she and her husband told their daughters the news during breakfast the next morning. The girls were confused and angry, she said. Olivia, in particular, asked about whether she'd be able to continue learning Spanish at her new school. Tolksdorf said she couldn't give her an answer, since district leaders haven't said whether De Zavala's dual-language program will go on at another campus once the school shuts down.

Since then, Tolksdorf and her husband have walked the girls to E.M. Daggett Elementary School to show them where they'll start third grade in a few years. But the girls are worried about what will happen to their friends, she said. Under the district's plan, students from De Zavala will be divided between Daggett and Lily B. Clayton elementary schools, so there's no guarantee that all of the girls' friends will end up in the same place.

Although the vote didn't go as she'd hoped, Tolksdorf said the issue has created an opportunity for her daughters to learn the importance of civic engagement. In the months leading up to the vote, she brought the girls to speak about their school during public comment sessions, and she and her husband have talked to them about why it's important to speak up about issues that are important to them.

It also gave Tolksdorf and her husband a chance to talk with the girls about managing their feelings when things don't go their way, she said. When their daughters start to get worried or upset, she reminds them to take a deep breath and practice their resilience.

"We have a statement in our family - ‘It's not what I want, but I'm going to be OK,'" she said.